Reciprocal community engagement goes beyond collaboration.

It’s about co-creating solutions, building trust, and fostering relationships that drive lasting impact. This toolkit highlights network partners who are pioneering equity-driven approaches rooted in cultural responsiveness and relational accountability. Explore their stories to see what authentic, community-centered engagement looks like in practice.

Why It Matters

In today’s shifting social and political landscape, the urgency of reciprocal community engagement in STEM education has never been greater. Systemic barriers continue to affect Black, Latinx, and Native American (BLNA) communities, making it essential that we approach this work with intentionality, shared power, and respect for lived experience. When we build with communities—not just for them—we strengthen belonging, representation, and sustainability in STEM.

What You'll Find Inside

- Partner-led strategies for equitable engagement and culturally responsive collaboration

- Reflections and lessons from Beyond100K network partners co-creating solutions in their communities

- Actionable practices that integrate decolonizing methodologies, prioritize relationship-building, and redistribute power

- Guiding questions to help adapt and apply these strategies within your own work

Explore the Toolkit

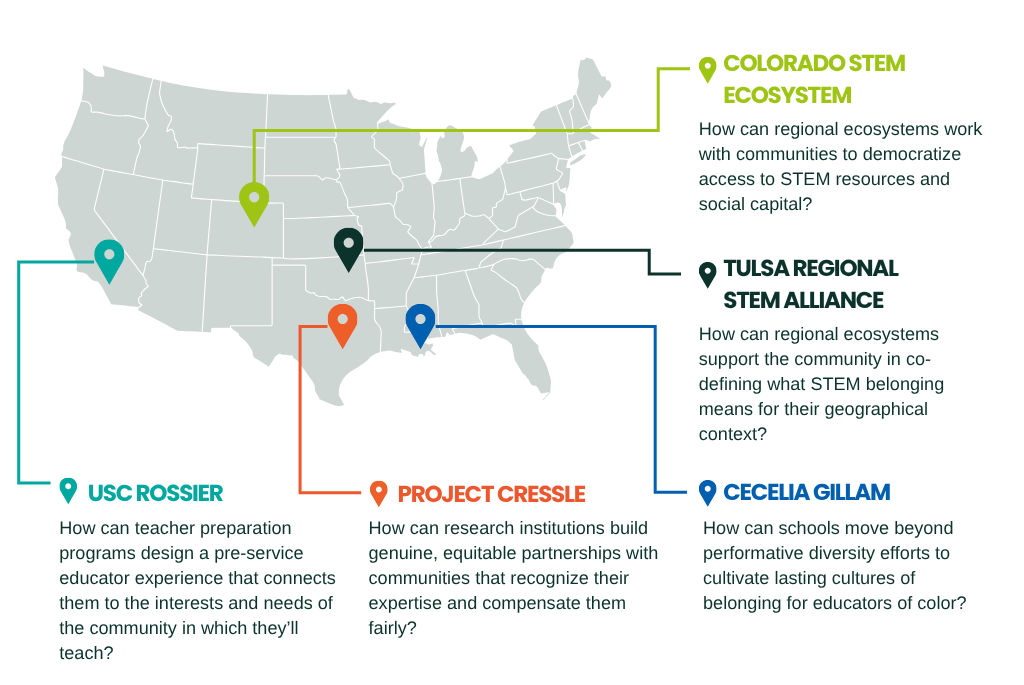

This resource is designed for Beyond100K partners working alongside BLNA communities to address the STEM teacher shortage through equitable, community-centered strategies. Read the toolkit and explore the questions of our Beyond100K network partners below.

Thank you to the 2024-2025 Keystone Fellows!

Emily Mortimer, Tulsa Regional STEM Alliance

Tracy Staley, Techbridge Girls

Jen Mossgrove, Knowles Teacher Initiative

Cecelia Gillam, Benjamin Franklin High School

Janelle Johnson, Colorado STEM Ecosystem

Taunya Nesin, WestED

Questions Explored

How can research institutions build genuine, equitable partnerships with communities that recognize their expertise and compensate them fairly?

In many underserved communities, the legacy of environmental injustice persists—poor water quality, disproportionate exposure to industrial pollution, and the residual effects of redlining continue to shape daily realities. Dr. Jay Banner, a geoscientist at the University of Texas at Austin, is grappling with this challenge head-on. Through his work with Project CRESSLE (Community Resilience through an Earth System Science Learning Ecosystem), Banner is rethinking how scientific research is conducted by centering the voices and priorities of the communities most affected by climate change. Austin, Texas, has a long history of segregation and environmental injustice, particularly in its East and Southeast neighborhoods, where historically redlined communities continue to experience higher pollution levels and urban heat island effects. As Banner witnessed these inequities, he recognized the limitations of traditional academic research models. The “helicopter science” approach—where researchers extract data from communities without meaningful engagement—was insufficient. Instead, Banner turned to Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) as a more impactful approach.

For Banner, partnerships are not just about working alongside community members; they are about co-creating solutions that address real, pressing concerns. “In CBPR, community members aren’t just consulted—they are equal collaborators at every stage, from ideation to implementation,” he explains. This model of CBPR prioritizes co-creation, where decisions are made collectively, and power is distributed across both academic researchers and community stakeholders. Unlike traditional engagement models that extract knowledge without meaningful reciprocity, this practice fosters long-term relationships, builds local capacity, and integrates community expertise as a core component of scientific inquiry. Through Project CRESSLE, Banner and his team have established a Community of Practice, bringing together researchers, community organizations, and local residents to co-develop and execute research projects that increase the resilience of underserved neighborhoods in Austin.” One of the most striking examples of this approach is in Austin’s Colony, a predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhood on the outskirts of Austin. Many residents there lack access to city-provided water and rely on independent water suppliers, often at higher costs and with lower quality. Banner’s team, in collaboration with local community fellows, has been measuring water quality, assessing regulatory compliance, and supporting residents in advocating for improvements. Rather than dictating research priorities, the initiative focuses on listening first, ensuring that the climate change concerns of the community drive the agenda.

While Banner’s work is making strides, he acknowledges that systemic barriers remain. Universities often undervalue CBPR, prioritizing fast-paced publication cycles over the slow, relationship-driven work of reciprocal community engagement. His hope? That institutions will recognize the academic and societal value of CBPR and invest in its sustainability through funding, tenure recognition, and dedicated programs. “If we’re serious about transforming geosciences and STEM research as a whole, we need to make CBPR part of the university’s fabric, not just a side project,” he asserts. The challenge of integrating scientific research with authentic community engagement is vast, but Banner’s work offers a powerful framework. By centering equity, valuing co-creation, and rethinking traditional research structures, his approach provides a roadmap for how STEM professionals can contribute to true environmental justice.

A Promising Practice

Community Fellowship Model

How can teacher preparation programs design a pre-service educator experience that connects them to the interests and needs of the community in which they’ll teach?

USC Rossier is embedded within the city of Los Angeles and their approach emphasizes the importance of leveraging the wealth of knowledge and skills in a child’s home. From the outset pre-service educators complete a variety of projects intended to build their understanding of the interests and needs of this diverse community. Pre-service educators immerse themselves as learners as they meet parents and administrators and understand their student’s strengths. Fred asserts, “if you can’t connect science content to the kids and what they bring to schools, they’re not going to learn.” Fred nudges his pre-service educators to continually reflect on who they are teaching, what science knowledge they already bring, and how to build upon it. By fostering a deep connection with the community, USC Rossier pre-service educators are equipped to create meaningful and impactful science learning experiences that resonate with students’ lives and backgrounds.

bridging stem with real-world community challenges

The 5E Lesson Plan is one tool USC Rossier leverages in their preparation of future science educators.This tool positions BLNA students to understand real-world STEM challenges relevant to their community and has the potential to connect them to community members. Pre-service science educators engage students in an immersive way as students use a real world relevant phenomenon, for instance, exploring the connection between sickle cell disease and gene mutation. Students inevitably make connections to people they love and care about. Fred shares, “The lesson becomes relevant and meaningful to the student because they may have a grandmother with sickle cell or a cousin with diabetes.” This also presents pre-service educators with the opportunity to engage community members who can contextualize the data or support the interpretations of findings. This collaborative approach can enrich the learning experience, keep students engaged and foster a deeper connection between students and their communities. By incorporating culturally relevant pedagogy, and diverse perspectives, these pre-service educators are inspiring the next generation of STEM leaders.

Fred embodies the USC Rossier School of Education’s mission and values as he continually reflects on his practice. Fred states, “The way we improve is we keep thinking about it, we keep reflecting on what’s working, what’s not working, and how we can do better.” Actively seeking out community partners and mobilizing these resources to ensure pre-service science educators foster a love of learning and science in their students is reflective of this mindset. He admits, “You can’t do everything as one educator, but you can connect to other organizations that have amazing stuff and bring it to your students.” Fred’s and USC Rossier’s asset-based lens demonstrates what is possible when preparation programs value and utilize the knowledge students, families and communities hold to unlock BLNA student potential.

A Promising Practice

5E Lesson Plan

How can regional ecosystems work with communities to democratize access to STEM resources and social capital?

STEM ecosystems have the power to shift who holds influence in education by rooting opportunity in community leadership. Dr. Janelle M. Johnson, director of the Colorado statewide STEM Ecosystem, is at the forefront of this movement—working to ensure that equity isn’t just a value but embedded in structure and approach. She recognizes that static leadership roles in STEM fields often create systemic barriers to access and representation. Dr. Johnson describes the Ecosystem as designed to broaden access: “You don’t have to be a power player to engage – you have a voice at the table to tell your story, do the networking and access resources.” By treating community members as co-owners—not participants—her work makes STEM feel both accessible and accountable. She highlights how traditional models often fail to serve local needs, leading to what she terms “talent drain,” where students must leave their communities to pursue STEM opportunities. This intentional integration of STEM education with economic empowerment ensures that people can remain connected to and invested in their local communities.

Co-creation is at the heart of effective and sustainable community engagement.

Under Dr. Johnson’s leadership, a digital STEM ecosystem visualization tool was built using the KUMU.IO platform. Dr. Johnson shares, “A lot of the technology that we come across might address STEM, but equity is an afterthought. The concept of building a tool to close the STEM opportunity gap was researched and cultivated from grassroots organizations. Long before the tool was built, community organizations were serving the needs of students and families and broadening access to high quality STEM learning experiences.” Members of community organizations complete a Google Form upon joining the Colorado STEM Ecosystem, and the data submitted is then automatically integrated onto the digital platform. The information is mapped in such a way to blur the lines between rural and urban communities and organizational size, leveling the playing field for more even participation and ownership. Her team continuously refines the STEM Ecosystem platform based on user feedback, making it a living, evolving tool that reflects the needs and aspirations of its co-owners. The Colorado STEM Ecosystem is not just a tool for networking—it is a mechanism for structural change, enabling communities to define and lead their own STEM equity efforts. In today’s charged political climate, this kind of hyperlocal, justice-centered collaboration isn’t just bold—it’s necessary.

Co-creation is at the heart of effective and sustainable community engagement. Dr. Johnson emphasizes the importance of listening to community voices and ensuring they play a central role in decision-making processes rather than imposing top-down solutions. With an open source ethos, Colorado has been sharing their digital infrastructure with ecosystems in other states and countries, and are currently working toward a fully open source product that others can customize for their efforts. Looking forward, Dr. Johnson envisions expanding impact by increasing engagement across different sectors and documenting and amplifying success stories to drive policy and funding decisions. By prioritizing community voice, transparency, and collaboration, Dr. Johnson’s approach offers a replicable framework for other communities striving to deepen their engagement in STEM education and workforce development.

A Promising Practice

Network Mapping

How can schools move beyond performative diversity efforts to cultivate lasting cultures of belonging for educators of color?

Cecelia has firsthand experience with the ways in which educator voices are suppressed or ignored. “I only have so much that’s within my sphere of influence and everything from the top trickles its way down.” This candid reflection comes from an investment of time and energy into campus initiatives that didn’t yield tangible change for herself or other educators. It forced her to reflect on where the change truly happens and what it takes for educators to be heard. She acknowledged that those moments left her feeling indifferent. Treating educators as genuine partners in a child’s learning means shared accountability for Cecelia. It’s not enough to invite educators, parents and community members into a conversation; real engagement happens when institutions take measurable actions that reflect the needs and aspirations of those they serve. Co-creation, in her view, is a process of listening, acknowledging, and acting in ways that build trust over time.

Cecelia’s work as a Black science educator is grounded in the reality that while many districts successfully recruit educators of color, they struggle to retain them. She experienced a disconnect between the messaging communicated to her at professional development workshops and her everyday experiences once back in the classroom. Reflecting on the experience she shared, “I was still subjected to microaggressions and macroaggressions. How might we stop that?” Determined to change her experience, Cecelia formed a Teachers of Color Committee with support from the Smithsonian Science Education Center and Shell. The goal was simple – develop core strategies that help educators of color know they belong and retain them professionally. Cecelia convened educators from across the district and provided a space for educators to share their experiences and identify systemic barriers. Initially, they were hesitant—they feared speaking out due to potential backlash. However, thanks to training provided by the Black Teacher Project, Cecelia introduced Constructivist Listening, a practice that fostered trust and encouraged open dialogue. Once trust was established, educators analyzed data to uncover the district’s retention issues and collaboratively strategized solutions. Cecelia’s work illuminates the spectrum of community engagement—moving beyond token representation toward meaningful participation. By challenging leadership to examine retention data and listen to educator concerns, she pushed for deeper accountability.

Cecelia is currently working to institutionalize accountability measures that prioritize belonging as a Project Team leader within the Beyond100K network. While her previous district projected a commitment to diversity, she recognized that their approach was largely transactional. She is exploring ways to integrate educator feedback into administrative evaluations, ensuring that belonging is not just a talking point but a fundamental metric of success. Cecelia shares, “My idea is aimed at cultivating a sense of belonging for Black and Brown educators by creating a framework for belonging within a school and holding administrators accountable for delivering.” Despite the setbacks encountered, she’s determined to end the STEM teacher shortage because she is deeply familiar with the data. Cecelia’s insights underscore the critical need to move beyond surface-level diversity initiatives and cultivate environments where educators of color feel genuinely valued and heard.

A Promising Practice

Constructivist Listening

How can regional ecosystems support the community in co-defining what STEM belonging means for their geographical context?

The Tulsa Regional STEM Alliance (TRSA) serves as a backbone organization engaging a cross-sector of organizations committed to ensuring Tulsa students access high-quality STEM experiences. Emily emphasizes the importance of community members understanding their ability to influence and contribute to TRSA’s work given the region’s complicated legacy. Greenwood, home to a thriving business district – Black Wall Street – was burned and looted in what is known as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Tahlequah, situated an hour east of Tulsa, was the final destination for the Cherokee people who walked the Trail of Tears. Emily recounts, “Over the last five years there’s been a focus on reconciliation and we have a lot of connections to organizations that are promoting these efforts.” For Emily, investing in community partnerships is about cultivating STEM belonging in a community that has not always been welcoming to Black and Native American communities.

Emily is a champion of community voice in North Tulsa as educators, community organizations, families, and university leaders gather to define STEM within their context. The North Tulsa STEM Hub unites community stakeholders to evaluate the current state of STEM, collaboratively develop a shared vision for its future, and articulate the role the hub is positioned to play. The inclusion of those closest to the challenge coupled with ongoing conversations with teachers and school administrators positioned the STEM Hub to narrow its focus around transportation, staff turnover amongst STEM providers, family engagement, and funding. Emily remains reflective as she guides the STEM Hub in co-creating their future. “How do we create the funding structure and the funding priorities that are not TRSA’s priorities but rather the hub’s priorities?” This point of tension is one Emily is open to exploring as the STEM Hub is but one of many initiatives launched by TRSA. Standing up a STEM Hub in what is defined as a STEM desert has allowed TRSA to mobilize community members in designing a sustainable STEM ecosystem that reflects North Tulsa’s long-term aspirations.

The community of Tulsa was recently awarded a Tech Hubs Designation by the U.S. Economic Development Administration. These endorsements are given to regions that demonstrate great potential in becoming “globally competitive innovation centers” within the next decade. TRSA’s work takes on added urgency within this context. Incorporating diverse community perspectives remains a priority and TRSA is in the process of creating more formalized agreement structures with community-led organizations. Although community engagement has always been valued they realize there is room for improvement. Emily explains “we want people to really own and know that they can impact and have a voice in our work, and the different ways that they can engage in the way that makes the most sense to them either as an individual or as an organization.” The reality is stark – BLNA students cannot compete globally without organizations like TRSA walking in lockstep with community members to remove structural barriers that hinder innovation and growth.